The Gorgon, Medusa, was known for her petrifying gaze. That mortal power continued after Perseus beheaded her so Athena used Medusa’s head on her shield.

Of course, there are multiple versions of this story, which continues to evolve today

In some versions Medusa had two sisters who were immortal, though for some (undisclosed) reason she was not. Daughters of primordial sea gods, they had long claws, fangs or tusks, and hissing serpents for hair. Their bulging eyes could turn a person to stone.

For some scholars the Gorgons represent the ancient matriarchal religions which were overthrown by the Olympians

In other versions, Medusa was a mortal girl who consorted with Poseidon, in some stories willingly, whom Athena punished by turning her into a monster.

Enter Perseus

Her fatal run-in with Perseus occurred when a king who was courting his mother asked him to bring the Gorgon’s head as a banquet gift.

Though Perseus was a son of Zeus, he wasn’t known for any skill at that time, so Hermes and Athena took pity. Hermes gave him a curved sword and Athena a shiny reflecting shield.

They sent him to the Graea who knew the location of the Hesperides, nymphs from the western lands, who in turn knew where to find Medusa.

Lots of eyes in this story…

The Graea were three old women, sisters and daughters of the same primordial sea gods. They had one eye and one tooth between them- which they shared, like sisters do. When Perseus held the eye ransom, they told him what he wanted.

The Hesperides really set him up

They not only gave him directions to the faraway land of the Gorgons, they provided winged sandals for faster travel, a satchel to carry Medusa’s head, and a nifty cap of invisibility.

According to some stories, Medusa was asleep when Perseus arrived, which pretty much rendered her harmless. In any case, he didn’t look at her directly but used the shield to see and cut off her head.

Her sisters woke up and went after him, but Perseus donned his cap so they couldn’t see him. The sandals ensured a speedy exit.

According to some accounts, he rescued his future wife Andromeda on his way home, but others say it happened later. But when he arrived to the court of the king, he pulled the Gorgon’s head out of his satchel and turned the pesky king and his guests to stone.

Then he gave Medusa’s head to Athena. She added it to her shield. Some say it was actually Zeus’s shield, but that she used it more than he did.

Apotropaic images and symbols ward off evil

By using Medusa’s face to defend herself, Athena appropriated her power.

Images of frightening animals or creatures have long been used to protect from evil, especially at doorways and windows. The eye is often used as an apotropaic image.

And there are so many references to vision in this story: the look that petrifies, the shared eye, the use of a mirror to see safely, escaping by becoming invisible.

What better defense than Medusa’s eyes?

Beauty or the beast?

Medusa often appears in the guise of a monster, while in other cases, like in Cellini’s Perseus, her features are human.

One interpretation is that this corresponds to an evolution through time, from monster to maiden.

However, as noted by Kathryn Topper, some vases from the 6th century BCE show Medusa as a sleeping maiden. She suggests that these depictions of Medusa are telling a slightly different story in which Perseus is no hero.

And sometimes the shield has a Medusa that isn’t a Medusa

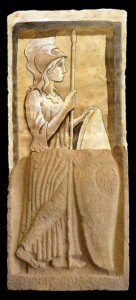

An incomplete relief of Minerva (the Roman version of Athena) from 300CE is found on the Roman walls of my hometown. Minerva stands in profile, her large shield before her. The shield holds no Medusa, but a wolf’s head.

The wolf was a sacred animal for the Iberians that lived on the Mediterranean coast of Spain when the Romans arrived. It represented strength and valor.

The Romans knew all about appropriating the power of those that came before

More recently, fashion designer Gianni Versace chose an image of Medusa as the logo for his company.

And thus throughout history, symbols are repurposed. Their meaning evolves, but more slowly than their power wanes.

Pingback: Janus and attending the start of all things - Systematic Wonder